Ever since I drew the original plans a year ago, I’d always had the idea that – should the CRNW have survived – that there might be a branch to Katalla. As those familiar with the CRNW know, at one point Katalla was to be the terminus of the CRNW. It had a key advantage for a burgeoning mining industry – nearby coal and oil reserves. The town lacked one key feature, however – a natural deep-water harbor.

In reality, Katalla’s demise began with the federal government (under President Teddy Roosevelt) withdrawing public lands from coal mining in 1906. Shortly thereafter, the lands were closed to timber and oil extraction as well. Then, in November 1907, all of the Katalla dock and breakwater facilities were destroyed in a series of early winter storms. With no available resources – save a single 160-acre oil field – and no facilities, the CRNW packed up and moved its terminal to Cordova. Katalla would get a refinery to process the limited (but apparently high quality) crude it produced, but little other industry developed to sustain the town. By 1933, when the refinery accidentally burned, there were reportedly only about 100 people still living in town. However, that was the end – after 1933, Katalla would fade into history.

In 1971, however, new hope arose for industry in the Katalla area. Thanks to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and its effort to compensate the Alaska native peoples for their losses, the Bering River bituminous fields and the Carbon Mountain anthracite fields passed to the Chugach Alaska Corporation, one of the regional corporations set up by the ANCSA to administer lands transferred back to the native people. In 1991, the rights to develop the field were sold to the Korean Alaska Development Corporation as part of CAC’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings. KADCO has yet to do anything with these rights, and in fact several conservation interests have discussed buying them to prevent any future mine.

Further, the CAC obtained rights to try for commercially-exploitable quantities of oil and gas in the Katalla Field in 1982. However, these rights were temporary, and expired at the end of 2004 unless a commercial well could be put in production.

In reality, no commercially viable oil well materialized, and the coal fields remain untouched since 1906. However, with the idea that my modern day CRNW could provide both a customer and a transportation solution, I’m going to explore the idea that at least the coal fields were developed at a small scale. Local coal seems a plausible energy source for both my processing plant at Eyak, the town of Cordova (which in reality today draws its power from both hydro and a large diesel plant), and the mine operation itself. Plus, having another local job to run adds more operating interest than just the ore trains and wayfreights plying the mainline.

As much as I’d like the branch to have been developed in the 1920s or 1930s, I’d have to bend history around too much to make that plausible. If the Guggenheims and JP Morgan couldn’t get the Department of the Interior to change their mind about resource extraction in the 1910-1930 era, there’s no plausible reason to believe that it would have happened between 1930 and the transfer of the coal loads to the CAC in 1972. So, in my version of the world, the Katalla Branch would have been developed in about 1972, once the dust had settled on the ANCSA.

One of the original 1913 Alaska Railroad Commission reports indicates that two routes were considered from the CRNW to the Bering coalfields. Both would start near the Miles Glacier Bridge. One route would run around the coastline to Katalla and then back up the Bering River. The other (shorter) route would run up the Martin River delta, cross over near the foot of the Martin River Glacier, and then pass over some steep grades (estimated at 1.7-2%) and around the western shore of Lake Charlotte. From there, it would reach the mines and could be extended down towards Katalla. By 1972, with modern motive power, construction techniques, and the recently-reinforced knowledge of the powerful damage earthquakes could transform the coastline, I have to assume that the the mountain route via Lake Charlotte would have been used. Plus, there was no reason for the Katalla Branch to actually go to Katalla by that point, as there wasn’t anything left of the town.

My other problem is rather pragmatic – I sketched in the Katalla Branch coming off the mainline between Alaganik and the Miles Glacier Bridge. In reality, it would have diverged in this area, coming off the mainline after it had crossed the braided tributaries of the Copper on the north/east side of Long Island. The problem is that’s located at the end of the peninsula on my layout, and I can’t come up with a good way to helix the track down at that point. There’s just too much benchwork needed to support the peninsula to start putting holes in it.

I don’t intend trains coming off the branch to ever be particularly long – maybe 8 cars plus engines and caboose, to be roughly in proportion to mainline trains at 20ish cars. Plus, back-of-the-cocktail-napkin calculations show that creating 200 tons of pure copper a day via electrowinning would take roughly 4-5 cars of coal per day, given typical generation efficiencies. So if I could pull 8 cars out every op session, that seems reasonable to feed the whole shebang.

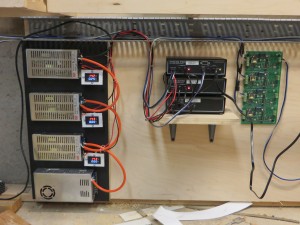

Enter the train elevator. Basically a strip of track 55-60 inches in length, mounted to a wood carriage that rides on two linear rails. A pair of stepper motors and jackscrews raise and lower the track between the two decks. I intend to make it 99% automated, so that the train pulls in, power gets cut when it hits a sensor, and the elevator takes it to the other level. From an operator’s point of view, they’ll leave Katalla Junction and disappear into the trees, and a minute or so later pop out of a summit tunnel or cut on the very lowest deck.

There’s absolutely nothing like it in the prototype. I know and accept that. I wouldn’t want one on the mainline – the main decks will be connected via a proper helix – but it seems an acceptable way to add time (otherwise the supposedly 38+ mile branch would only be maybe 15 feet long) and an easy connection to what amounts to a long industrial spur. It gives me a plausible connection to local fuel producer, and a reason to run another local job every op session or two.

I’ve got the rails, the screws, and the stepper motors – now it’s just a matter of getting all the other widgets (screws, brackets, etc.), designing some controls, and testing it out. I’ll let you know what comes of it.